This section contains abstracts or excerpts from the growing number of articles, by various authors, who generally agree that “conscientious objection” is harmful and inappropriate in health care.

(2020) Beyond Money: Conscientious Objection in Medicine as a Conflict of Interest

Alberto Giubilini & Julian Savulescu

Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, Vol 17, pgs 229–243 (May 2020)

Abstract

Conflict of interests (COIs) in medicine are typically taken to be financial in nature: it is often assumed that a COI occurs when a healthcare practitioner’s financial interest conflicts with patients’ interests, public health interests, or professional obligations more generally. Even when non-financial COIs are acknowledged, ethical concerns are almost exclusively reserved for financial COIs. However, the notion of “interests” cannot be reduced to its financial component. Individuals in general, and medical professionals in particular, have different types of interests, many of which are non-financial in nature but can still conflict with professional obligations. The debate about healthcare delivery has largely overlooked this broader notion of interests. Here, we will focus on health practitioners’ moral or religious values as particular types of personal interests involved in healthcare delivery that can generate COIs and on conscientious objection in healthcare as the expression of a particular type of COI. We argue that, in the healthcare context, the COIs generated by interests of conscience can be as ethically problematic, and therefore should be treated in the same way, as financial COIs.

Relevant Excerpt (from Conclusion)

If we frame conscientious objection as the expression of a conflict of interest in health care, then it is apparent how at the moment conscientious objection is treated and managed differently from the way other conflicts of interest are treated, and for no apparent good reason. Allowing conscientious objection to certain practices means not only acknowledging that a conflict of interest exists (because we are acknowledging that the health care professional has personal goals and motivations that conflict with professional obligations) and that the conflict is ethically impermissible (because we are acknowledging the professional’s personal goals and motivations prevent them from fulfilling their professional obligations). It also means allowing the conflict of interest to take place and to affect professional conduct when we do not allow the same to happen in the case of FCOIs. This differential treatment is not ethically justified, or so we have argued.

Source: Journal of Bioethical Inquiry (open access)

(May 2020) The inequity of conscientious objection: Refusal of emergency contraception

Chelsey Yang, May 13, 2020, Nursing Ethics, 27:6; 1408-1417.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020918926

Abstract

In the medical field, conscientious objection is claimed by providers and pharmacists in an attempt to forgo administering select forms of sexual and reproductive healthcare services because they state it goes against their moral integrity. Such claim of conscientious objection may include refusing to administer emergency contraception to an individual with a medical need that is time-sensitive. Conscientious objection is first defined, and then a historical context is provided on the medical field’s involvement with the issue. An explanation of emergency contraception’s physiological effects is provided along with historical context of the use on emergency contraception in terms of United States Law. A comparison is given between the United States and other developed countries in regard to conscientious objection. Once an understanding of conscientious objection and emergency contraception is presented, arguments supporting and contradicting the claim are described. Opinions supporting conscientious objection include the support of moral integrity, religious diversity, and less regulation on government involvement in state law will be offered. Finally, arguments against the effects of conscientious objection with emergency contraception are explained in terms of financial implications and other repercussions for people in lower socioeconomic status groups, especially people of color. Although every clinician has the right and responsibility to treat according to their sense of responsibility or conscience, the ethical consequences of living by one’s conscience are limiting and negatively impact underprivileged groups of people. It is the aim of this article to advocate against the use of provider’s and pharmacist’s right to claim conscientious objection due to the inequitable impact the practice has on people of color and individuals with lower incomes.

Source: Nursing Ethics

(2020) Implementing the liberalized abortion law in Kigali, Rwanda: Ambiguities of rights and responsibilities among health care providers

Jessica Påfs, Stephen Rulisa, Marie Klingberg-Allvin, Pauline Binder-Finnema, Aimable Musafili, Birgitta Essén et al

January 2020

Midwifery, Vol 80, 102568

Partial Abstract

Objective: Rwanda amended its abortions law in 2012 to allow for induced abortion under certain circumstances. We explore how Rwandan health care providers (HCP) understand the law and implement it in their clinical practice.

Findings: HCPs express ambiguities on their rights and responsibilities when providing abortion care. A prominent finding was the uncertainties about the legal status of abortion, indicating that HCPs may rely on outdated regulations. A reluctance to be identified as an abortion provider was noticeable due to fear of occupational stigma. The dilemma of liability and litigation was present, and particularly care providers’ legal responsibility on whether to report a woman who discloses an illegal abortion.

Conclusion: The lack of professional consensus is creating barriers to the realization of safe abortion care within the legal framework, and challenge patients right for confidentiality. This bring consequences on girl’s and women’s reproductive health in the setting. To implement the amended abortion law and to provide equitable maternal care, the clinical and ethical guidelines for HCPs need to be revisited.

Relevant Excerpt

Our findings point at a lack of professional consensus when consulting persons seeking advice or care for an unwanted pregnancy. The HCPs consult women differently depending on their personal values and interpretation of the law. This bring thoughts to the ‘Professional Code of Ethics’ as nurses and midwives have the right to “refuse to participate in activities contrary to his/her personal moral and professional convictions.” (Rwanda Ministry of Health 2009). This is an issue raised within reproductive health care, as the allowance for personal values among HCPs leads to an inequitable provision of care (Rehnström Loi et al., 2015 ; Fiala and Arthur, 2014). For physicians, the ethical guidelines do state that it is in their duty to provide abortion within the law ( Rwanda Ministry of Health 2009 ), in line with what one of the participants said. Yet, the physicians in our study also claimed they lack proper training to implement this in practice. This argument of not possessing the skills needed may though be a cover up for their actual attitudes of not being willing to provide abortion services. Similar reasoning has been seen among nurses and midwives in other sub- Saharan countries (Rehnström Loi et al., 2015). The lack of skills cannot be an acceptable argument anymore, given the possibility of medical abortions, that can be carried out by midlevel providers and women themselves and are in line with WHOs recommendations (Klingberg-Allvin et al., 2015; Cleeve et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2019). Not only could such task-shifting significantly reduce cur rent costs of PAC and diminish current workload of health care providers in Rwanda (Vlassoffet al., 2015) – it may also facilitate for HCPs in their ethical dilemma seen in our findings. However, HCPs attitudes play an important role in the implementation of task-shifting (Kim et al., 2019). Additionally, our findings highlight the concern of stigma connected to the implementation and usage of Misoprostol in the clinical practice. The controversial status of Misoprostol is worthy of attention. This does not only have implications for abortion-related care, but also for the quality of maternal health care.

Source: Midwivery

(Aug 2018) On the Revolutionary Road to Reproductive Justice

by Michelle Truong, International Women’s Health Coalition

August 6, 2018

Dr. Willie Parker is an abortion provider because of, not despite, his Christian faith. At a moment when refusal of care due to conscience claims obstructs reproductive justice, emphasizing the role conscience plays in compassionate and ethical medical care, as Dr. Parker does, means a revolutionary shift in thinking about power—prioritizing the needs of the woman seeking care.

The use of conscience claims to deny health care services is a focal point in current debates on abortion access and was a central issue at the recent Abortion and Reproductive Justice Conference (ARJC) in South Africa. In an auspicious start to the ARJC, the host-city, formerly known as Grahamstown, had recently voted to discard the name of Graham, a brutal colonizer, to rename in honor of Makhanda, a Xhosa freedom fighter and philosopher.

Source: Read article

(July 2018) Religious Refusals and Reproductive Rights: Claims of Conscience as Discrimination and Shaming

By Louise Melling

Chapter 14 – Religious Refusals and Reproductive Rights, from Part IV – Conscience, Accommodation and Its Harms. Edited by Susanna Mancini, Università di Bologna, Michel Rosenfeld. Publisher: Cambridge University Press

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316780053.015

Relevant excerpt:

The stories from Indiana and Arizona illustrate the different way in which we currently view refusals to serve LGBT people for reasons of religious beliefs versus refusals to serve women seeking reproductive health services because of religious beliefs. This chapter takes issue with this difference. It argues we need to see, question, and protest the harms that result when women seeking services related to contraception and abortion are turned away for reasons of faith as robustly as we question the harms when LGBT people are refused service because of religious beliefs.14 It asks that we see these refusals as discrimination too.

In making this call for change, this chapter first puts the current debate in the United States about religious refusals in context; second, it posits parallels between the harm to women turned away for wanting to control their fertility and to same-sex couples denied services for their weddings; third, this chapter offers an account for why refusals to provide services because of religious beliefs are treated differently in the two contexts; and finally, it argues that how we think about religious objections to serving those seeking abortion and contraception matters for women’s equality. This chapter does not purport to put forward a definitive argument; it aims instead to make a case for questioning a long-standing norm.

(July 2018) Seeking to Square the Circle: A Sustainable Conscientious Objection in Reproductive Healthcare

Emmanuelle Bribosia and Isabelle Rorive

Chapter 15 in: The Conscience Wars: Rethinking the Balance between Religion, Identity, and Equality, ed. Susanna Mancini and Michel Rosenfeld (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018) pp. 392-413.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316780053.016

From Book Introduction:

[In this chapter, the authors] focus on the practical and conceptual difficulties in reconciling the reproductive rights of women with the conscience claims of individual health care providers. From a practical standpoint, drawing on national, international, and European measures, cases, and policy papers, they demonstrate that even the most balanced regulatory framework of conscientious objection fails to overcome the strength of the web of religious and patriarchal structures of society, in which women are still caught. This results in a distortion of religious exemption clauses to the detriment of women’s rights.

From a conceptual standpoint, Bribosia and Rorive … maintain that conscience clauses involve not only direct harm to women who wish to access abortion services but also dignitary and symbolic harm. In this light, conscientious objection places the medical doctor in the position of exercising personal power over the patient by imposing his or her beliefs, and that per se constitutes a violation of women’s dignity and equality. In the end, according to Bribosia and Rorive, access to abortion is not enough to protect women from discrimination: what is required is access to health care on an equal footing, without any moral judgment by an authority.

(July 2018) IWHC Brief to Constitutional Court of Colombia: Abortion Restrictions are Ineffective and Harmful

New York City, United States, 18 July 2018

To: Señora Magistrada CRISTINA PARDO SCHLESINGER, Corte Constitucional, E.S.D.

The International Women’s Health Coalition (IWHC) submitted an amicus brief to the Constitutional Court of Colombia, urging the court to defend women’s rights and health by upholding the right to safe and legal abortion. In October 2018, the court voted 6 to 3 to maintain no time frame restriction on legal abortion, denying a request to limit abortion to the first 24 weeks of pregnancy.

Excerpt: Research into the experiences of women confronted with the denial of abortion indicates that they face an increased risk of physical and psychological harm, socioeconomic disadvantage, and even shortened lifespans. In August 2017, IWHC, in conjunction with Mujer y Salud en Uruguay, organized the Convening on Conscientious Objection: Strategies to Counter the Effects, in which 45 participants from 22 countries discussed the consequences of denial of sexual and reproductive health care and shared data from their home countries. Convening participants who work at the community level recounted experiences of women who have suffered the negative effects of conscience claims.

Source: Read brief

(July 2018) Provider Conscientious Refusal, Medical Malpractice, and the Right to Civil Recourse

by Jane A. Hartsock

American Journal of Bioethics, 18:7, 66-68

DOI: 10.1080/15265161.2018.1478020

Nelson (2018) argues that where death results from conscientious refusal to provide abortion services in an obstetrical emergency, clinicians and institutions should be held criminally liable for homicide. I wholeheartedly endorse Nelson’s position and add the following additional observations: (1) Clinicians and institutions that decline to provide reproductive health care in accordance with generally accepted standards of care are civilly liable for professional and institutional negligence; (2) state statutes that attempt to obviate clinician and institutional duties to comply with the standard of care violate the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment of the United States Constitution and similar federal statutes violate the 5th and 7th Amendments; and (3) the preceding analysis holds true with respect to a wide range of women’s health care services in addition to abortion, including access to medically indicated birth

control and sterilization, and care and treatment of female survivors of sexual assault, to name just a few in this short response. There appears to be exceedingly little literature exploring this issue, and even less case law, but the 2016 case of Tamesha Means v. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops provides some insight and direction into what such a case might look like.

Source: Read article: American Journal of Bioethics

(July 2018) Enforcing Conscientious Objection to Abortion in Medical Emergency Circumstances: Criminal and Unethical

by Udo Schuklenk & Benjamin Zolf

American Journal of Bioethics, 18:7, 60-61

DOI: 10.1080/15265161.2018.1478036

Lawrence Nelson discusses cases in which abortion is necessary due to a life-threatening medical emergency. He argues that under American law, health care pro-

viders who conscientiously refuse to perform one in such circumstances are guilty of murder or reckless homicide, if the woman dies as a result of their refusal. A criminal homicide conviction requires an established standard of care that goes unmet, combined with a causal link between the failure to meet that standard and the death that eventuates (Nelson 2018). Physicians and hospitals uncontroversially have a legal duty to care for their patients. If their refusal to render that care causes someone’s death, they seem to clearly meet the criteria for criminal homicide. Nelson shows that this fact cannot be mitigated by claims about earnest moral intentions, or the right to free exercise of religion (Nelson 2018). He contends that expert medical witnesses would establish in court that physicians faced with emergency circumstances have a duty to provide medically necessary care, regardless of their conscientious beliefs. Finally, he argues that statutes exempting physicians from providing abortions in emergencies (which exist in a staggering 45 U.S. states) are unconstitutional.

Read full article: American Journal of Bioethics

(July 2018) Being a Doctor and Being a Hospital

Rosamond Rhodes & Michael Danziger

The American Journal of Bioethics, 18:7, 51-53

Doi: 10.1080/15265161.2018.1478021

In his excellent piece, “Provider Conscientious Refusal of Abortion, Obstetrical Emergencies, and Criminal Homicide Law,” Lawrence Nelson makes a compelling legal argument against physicians’ refusal to provide life-saving abortions (Nelson 2018). We want to make the equivalent moral argument. Nelson says that physicians who refuse to perform abortions are violating the “legal duty to treat the woman,” but he suggests that they may be “honoring a moral duty not to kill a fetus.” We take issue with that suggestion. Instead, we maintain that just as a physician who refuses to provide abortion violates a legal duty, that physician violates a moral duty as well.

Abstract and excerpt: American Journal of Bioethics

(July 2018) No conscientious objection without normative justification: Against conscientious objection in medicine

by Benjamin Zolf, Bioethics. DOI: 10.1111/bioe.12521

Abstract

Most proponents of conscientious objection accommodation in medicine acknowledge that not all conscientious beliefs can justify refusing service to a patient. Accordingly, they admit that constraints must be placed on the practice of conscientious objection. I argue that one such constraint must be an assessment of the reasonability of the conscientious claim in question, and that this requires normative justification of the claim. Some advocates of conscientious object protest that, since conscientious claims are a manifestation of personal beliefs, they cannot be subject to this kind of public justification. In order to preserve an element of constraint without requiring normative justification of conscientious beliefs, they shift the justificatory burden from the belief motivating the conscientious claim to the condition of the patient being refused service. This generally involves a claim along the lines that conscientious refusals should be permitted to the extent that they do not cause unwarranted harm to the patient. I argue that explaining what would constitute warranted harm requires an explanation of what it is about the conscientious claim that makes the harm warranted. ‘Warranted’ is a normative operator, and providing this explanation is the same as providing normative justification for the conscientious claim. This shows that resorting to facts about the patient’s condition does not avoid the problem of providing normative justification, and that the onus remains on advocates of conscientious objection to provide normative justification for the practice in the context of medical care.

Source: Bioethics

(June 2018) Unconscionable: When Providers Deny Abortion Care

by International Women’s Health Coalition and Mujer y Salud en Uruguay

by International Women’s Health Coalition and Mujer y Salud en Uruguay

(Dr. Christian Fiala is a contributor)

June 2018

The International Women’s Health Coalition (IWHC) and Mujer y Salud en Uruguay (MYSU) co-organized a global Convening on Conscientious Objection: Strategies to Counter the Effects, in August 2017. The meeting was designed to analyze and address the phenomenon of health care providers refusing to provide abortion care by using personal belief as a justification. The organizers were called to action by the global expansion of this barrier to abortion access and the experiences of women who were denied their right to an essential service. Forty-five participants from 22 countries convened in Montevideo, Uruguay, including activists and advocates, health care and legal professionals, researchers, academics, and policy-makers. The convening catalyzed an agreement that proponents of women’s rights should challenge the use of conscience claims to deny access to abortion care. The participants also identified strategies to counter the adverse effects that the refusal to provide care can have on the health and rights of those needing services.

Throughout three days of presentations and working groups (appendix B), participants shared their experiences and expertise on policies and legal frameworks, ethics, health care training and provision, activism, research, and communications. The result: recommendations that advocates can use to tackle the growing trend of health providers using claims of “conscientious objection” to deny abortion services. In this report, we present the key points and strategies discussed at the convening, with practical recommendations at the end of each section, and a summary of takeaways in the conclusion.

Click here to download the report [PDF]

Click here to view Policy Brief based on the report.

Excerpts from Executive Summary

The global women’s movement has fought for many years to affirm safe and legal abortion as a fundamental right, and the global trend has been the liberalization of abortion laws. Progress is not linear, however, and persistent barriers prevent these laws and policies from increasing women’s access to services. One such obstacle is the growing use of conscience claims to justify refusal of abortion care.

Often called “conscientious objection,” a concept historically associated with the right to refuse to take part in the military or in warfare on religious or moral grounds, the term has recently been co-opted by anti-choice movements. Indeed, accommodations for health care providers to refuse to provide care are often deliberately inserted into policies with the aim of negating the hard-fought right to abortion care.

Existing evidence reveals a worrisome and growing global trend of health care providers who are refusing to deliver abortion and other sexual and reproductive health care. This phenomenon violates the ethical principle of “do no harm,” and has grave consequences for women, especially those who are already more vulnerable and marginalized.

A woman denied an abortion might have no choice but to continue an unintended pregnancy. She may resort to a clandestine, unsafe abortion, with severe consequences for her health or risk of death. She might be forced to seek out another provider, which can be costly in time and expense. All of these scenarios can lead to health problems, mental anguish, and economic hardship.

International human rights standards to date do not require states to guarantee a right to “conscientious objection” for health care providers. On the contrary, human rights treaty monitoring bodies have called for limitations on the exercise of conscience claims when states do allow them, in order to ensure that providers do not hinder access to services and thus infringe on the rights of patients. They call out states’ insufficient regulation of the use of “conscientious objection,” and direct states to take steps to guarantee patient access to services.

….

Patients’ health and rights should never be subordinate to providers’ individual concerns. Health care providers who put their personal beliefs over their professional obligations toward their patients threaten the health care profession’s integrity and its objectives. Nothing would stop such individuals from joining the health care profession, but they ought to specialize in fields in which their abilities to provide comprehensive services is not undermined by their personal beliefs.

Joining the health care profession is voluntary, unlike conscripted military service. The military objector pays a price, often undergoing a government vetting process, carrying out obligatory alternative service, and frequently facing stigma and discrimination. In the case of the refusal of health care based on conscience claims, the providers do not pay a price, while others do. The most severely affected, of course, is the person denied care. Providers who refuse to deliver a service also increase the workloads of their peers who choose to uphold their professional obligations to provide comprehensive care. Finally, accommodating providers who refuse to perform essential aspects of their jobs can cause costly disruptions and inefficiencies in the health care system and divert precious resources away from service provision.

Currently, more than 70 jurisdictions have provisions that allow so-called “conscientious objection” in health care, according to an analysis of preliminary data from the World Health Organization’s Global Abortion Policies Database. Many national laws stipulate that health care providers are required to carry out an abortion in case of an emergency, or if no one else is available. Evidence clearly shows, however, that even where regulations are in place, they are extremely difficult—and costly—to enforce. Despite the difficulty of regulating conscience claims, participants agreed that governments should enforce regulations and ensure that all women are able to access affordable, comprehensive health care.

Most convening participants agreed that health care policies should not allow for the refusal to provide services based on conscience claims. Where policy-makers are revising abortion laws or policies, they should not make references to conscience claims. Enshrining into law the notion that providers’ personal beliefs can determine the provision of health care opens up the door to abuses and legitimizes conscience claims.

Finally, the convening participants resoundingly agreed that health care providers and women’s rights advocates must not cede the term “conscience” to those who misapply it to deny others health care, which should more appropriately be called “refusal to provide services” or “denial of services based on conscience claims.” They agreed to bring the agreements from the convening, and the recommendations captured at the end of this report, to their own work, so that no one is denied their right to health care.

(Jun 2018) Conscientious objection in medicine: accommodation versus professionalism and the public good

by Udo Schuklenk

Br Med Bull. 2018 Jun 1;126(1):47-56.

Doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldy007

Abstract

In recent years questions have arisen about the moral justification for the accommodation of health care professionals who refuse, on conscience grounds as opposed to professional grounds, to provide particular professional services to eligible patients who request that kind of service.

Central to concerns about the accommodation claims of conscientious objectors is that health care professionals volunteer to join their professions that typically they are the monopoly providers of such services and that a health care professional’s refusal to provide professional services on grounds that are not professional judgements amounts to unprofessional conduct. Defenders of conscientious objection maintain that in a liberal society respect for a professional’s conscience is of sufficient importance that conscientious objectors ought to be accommodated. To deny conscientious objectors accommodation would reduce diversity in the health care professions, it would deny objectors unfairly equality of opportunity, and it would constitute a serious threat to the moral integrity of conscientious objectors.

Source: British Medical Bulletin

(June 2018) No GP should be allowed opt out of abortions

by Newton Emerson

Thu, Jun 14, 2018

The UK supreme court sat for the first time in Belfast last month, hearing an appeal into the “gay cake” case, among others.

“People will of course not expect an answer any time soon,” the president of the court said upon reserving judgment.

Another thing nobody expects is for the court to let bakers opt into a register of those willing to ice gay cakes, comprising only a handful of bakers in the country, with people obliged to travel to find them.

(June 2018) Conscientious objection: a morally insupportable misuse of authority

Arianne Shahvisi

June 1, 2018

Volume: 13 issue: 2, page(s): 82-87

https://doi.org/10.1177/1477750917749945

Abstract

In this paper, I argue that the conscience clause around abortion provision in England, Scotland and Wales is inadequate for two reasons. First, the patient and doctor are differently situated with respect to social power. Doctors occupy a position of significant moral and epistemic authority with respect to their patients, who are vulnerable and relatively disempowered. Doctors are rightly required to disclose their conscientious objection, but given the positioning of the patient and doctor, the act of doing so exploits the authority of the medical establishment in asserting the legitimacy of a particular moral view. Second, the conscientious objector plays an unusual and self-defeating moral role. Since she must immediately refer the patient on to another doctor who does not hold a conscientious objection, she becomes complicit, via her necessary causal role, in the implementation of the procedure. This means that doctors are not able to prevent abortions, rather, they are required to ensure that they are carried out, albeit by others. Since removing the disclosure and referral requirements may prevent patients from accessing standard medical care, the conscience clause should instead be revoked, and those opposed to abortion should be encouraged to select other specialities or professions. This would protect patients from judgement, and doctors from complicity.

Source: Sage Journals

(May 2018) Public cartels, private conscience

Michael Cholbi

May 30, 2018

Sage Journals

https://doi.org/10.1177/1470594X18779146

Abstract

Many contributors to debates about professional conscience assume a basic, pre-professional right of conscientious refusal and proceed to address how to ‘balance’ this right against other goods. Here I argue that opponents of a right of conscientious refusal concede too much in assuming such a right, overlooking that the professions in which conscientious refusal is invoked nearly always operate as public cartels, enjoying various economic benefits, including protection from competition, made possible by governments exercising powers of coercion, regulation, and taxation. To acknowledge a right of conscientious refusal is to license professionals to disrespect the profession’s clients, in opposition to liberal ideals of neutrality, and to engage in moral paternalism toward them; to permit them to violate duties of reciprocity they incur by virtue of being members of public cartels; and to compel those clients to provide material support for conceptions of the good they themselves reject. However, so long as (a) a public cartel discharges its obligations to distribute the socially important goods they have are uniquely authorized to provide without undue burden to its clientele, and (b) conscientious refusal has the assent of other members of a profession, individual professionals’ claims of conscience can be accommodated.

Source: Sage Journals

(Jan 2018) A twist on conscientious objection: a regulatory proposal based on the practice of legal abortion in Argentina

Translated from Spanish: “Una vuelta de tuerca a la objeción de conciencia: Una propuesta regulatoria a partir de las prácticas del aborto legal en Argentina”

by Agustina Ramón Michel and Sonia Ariza, on behalf of CEDES and Ipas

January 2018

Note: The authors do support allowing “CO” – however, they propose strict regulation of it, including enforcement measures. Most of the paper is spent critiquing “CO” and documenting its harms and gross overreach in the context of legal abortion care in Argentina. Notably, the authors recommend dropping the term “conscientious objection” in favour of the more accurate and fair phrasing: “refusal to provide abortion services on moral or religious grounds.”

Abstract:

This paper addresses the case of health professionals who refuse to provide legal abortions based on religious or moral beliefs, known as conscientious objection (CO). In much of the West, conscientious objection is permitted in the context of health services. There are several forms of objection: pharmacists who refuse to sell contraceptives; physicians who invoke religious beliefs as grounds for denying fertility services to single or same-sex couples or for tubal ligations or abortion; health professionals who invoke the rights of persons with disabilities to refuse prenatal diagnosis, or gender equality legislation to oppose body-fitting interventions; nurses who refuse to provide services to women who request or have had an abortion because of religious beliefs; medical students who refuse to use animals during medical training on moral grounds, among others.

In this paper on CO to abortion in Argentina, we focus on two fundamental and interdependent aspects: the reconceptualization of this phenomenon and a proposal to regulate it within the framework of a public health policy. In addition to secondary sources, we obtained opinions and perceptions from a survey of 269 members of the public health system and 11 semi-structured interviews with managers and chiefs of services in the public health system about the forms that CO takes, its causes and impact.

Selected Extracts:

In the health context, CO clauses have been legislative tools used by certain professionals to excuse themselves from certain mandated tasks legally but which they consider objectionable on moral grounds.24 Indeed, CO has been a political tool to resist legislative and of public policies that challenge and dismantle the structure of sexuality traditional.25 According to Fiala and Arthur, CO “has allowed people to boycott democratically approved laws based on the deference of society to religious freedom and traditional values that assign women roles of maternity and child rearing”.26

In Argentina, these uses of CO are also observed.27 We have seen that the hierarchy of the Catholic Church has called for the use of objection as a mechanism to prevent access to contraceptives and abortion.28 Likewise, Catholic professional associations have developed guidelines for their members that privilege the use of CO.29 It has even been used in ways more associated with civil disobedience.30

————————————

This historicization of CO in the field of sexuality and reproduction should be contrasted with that of compulsory military service, the origin of this practice. They are related stories but differ in fundamental aspects. Alegre points out that in the field of sexual and reproductive health we are facing a “new objection”, different from the traditional objection to military service.40 On this point, Fiala & Arthur believe that it is dishonest for the CO in reproductive health care to bear that name, as it has little to do with what happens in the framework of compulsory military services: they have a different ethical basis.41

————————————

…CO functions as an institutional escape valve, to avoid all the costs generated by the provision of abortion services in this precarious context. It is a mechanism used not only by professionals but also by entire teams and health authorities, so as not to be responsible for the obligations of respect, protection and of the right to access an abortion, and to take shelter in hostile environments.

………….

Of course, there are also those who have used CO, under the argument of protection of individual moral integrity and moral plurality, to pursue political or ideological objectives (including religious, social, etc.) linked to a traditional sexuality, sexual roles and family forms that are considered the only normal ones. In this way, CO becomes the Trojan Horse in the contested field of reproductive rights.57 This is the case of the use of CO by the Catholic Church from its high hierarchies, who have urged their faithful to use it as a way to counteract the favourable changes to reproductive rights, as Vaggione points out.58 In Argentina, Pope Francis has called on doctors to use CO against abortion and euthanasia, for example.59 So, what was enshrined as a guarantee to protect the moral integrity of people, turns out to be an instrument to deny rights to pregnant women and ignore their integrity and moral agency.

———————————————

The proposed regulation is based on replacing the term CO with “refusal to provide abortion services on moral or religious grounds”, as this is considered a more accurate and fairer term to those who knowingly provide or request these services. Bearing in mind that a significant proportion (42%) of the people surveyed for the construction of this proposal considered that the stigma associated with the provision of services is one of the reasons that lead professionals to CO, we believe that it is fundamental to promote a change in the legitimacy of the provision of services and in that sense, we suggest this new designation.

Source, full article in Spanish: CLACAI – Latin America

(Apr 2017) Against the accommodation of subjective healthcare provider beliefs in medicine: counteracting supporters of conscientious objector accommodation arguments

by Ricardo Smalling and Udo Schuklenk

J Med Ethics. 2017 Apr;43(4):253-256.

doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103883

We respond in this paper to various counter arguments advanced against our stance on conscientious objection accommodation. Contra Maclure and Dumont, we show that it is impossible to develop reliable tests for conscientious objectors’ claims with regard to the reasonableness of the ideological basis of their convictions, and, indeed, with regard to whether they actually hold they views they claim to hold. We demonstrate furthermore that, within the Canadian legal context, the refusal to accommodate conscientious objectors would not constitute undue hardship for such objectors. We reject concerns that refusing to accommodate conscientious objectors would limit the equality of opportunity for budding professionals holding particular ideological positions. We also clarify various misrepresentations of our views by respondents Symons, Glick and Jotkowitz, and Lyus.

Source: Journal of Medical Ethics

(April 2017) Physicians, Not Conscripts — Conscientious Objection in Health Care

Ronit Y. Stahl, Ph.D., and Ezekiel J. Emanuel, M.D., Ph.D.

New England Journal of Medicine, 376;14, April 6, 2017

“Conscience clause” legislation has proliferated in recent years, extending the legal rights of health care professionals to cite their personal religious or moral beliefs as a reason to opt out of performing specific procedures or caring for particular patients. Physicians can refuse to perform abortions or in vitro fertilization. Nurses can refuse to aid in end-of-life care. Pharmacists can refuse to f ill prescriptions for contraception. More recently, state legislation has enabled counselors and therapists to refuse to treat lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) patients, and in December, a federal judge issued a nationwide injunction against Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act, which forbids discrimination on the basis of gender identity or termination of a pregnancy.

Health care conscience clauses are legislative tools that are used to insulate professionals from performing tasks that they personally deem objectionable. Legislative protection for conscientious objection in health care emerged at the height of

conscientious objection to military service. Supporters of conscientious objection in health care explicitly referenced “the right of conscience which is protected in our draft laws” to justify and legitimate it. Yet conscientious objection in health care diverges substantially from conscientious objection to war. We highlight the differences and argue that, in most cases, professional associations should resist sanctioning conscientious objection as an acceptable practice. Unlike conscripted soldiers, health care professionals voluntarily choose their roles and thus become obligated to provide, perform, and refer patients for interventions according to the standards of the profession.

Source: New England Journal of Medicine

(Jan 2017) The Cost of Conscience: Kant on Conscience and Conscientious Objection

Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, Volume 26, Issue 1, January 2017 , pp. 69-81

Jeanette Kennett

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963180116000657

Abstract:

The spread of demands by physicians and allied health professionals for accommodation of their private ethical, usually religiously based, objections to providing care of a particular type, or to a particular class of persons, suggests the need for a re-evaluation of conscientious objection in healthcare and how it should be regulated. I argue on Kantian grounds that respect for conscience and protection of freedom of conscience is consistent with fairly stringent limitations and regulations governing refusal of service in healthcare settings. Respect for conscience does not entail that refusal of service should be cost free to the objector. I suggest that conscientious objection in medicine should be conceptualized and treated analogously to civil disobedience.

(Jan 2017) The Legal Ethical Backbone of Conscientious Refusal

Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, Volume 26, Issue 1, January 2017 , pp. 59-68

Christian Munthe and Morten Ebbe Juul Nielsen

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963180116000645

Abstract:

This article analyzes the idea of a legal right to conscientious refusal for healthcare professionals from a basic legal ethical standpoint, using refusal to perform tasks related to legal abortion (in cases of voluntary employment) as a case in point. The idea of a legal right to conscientious refusal is distinguished from ideas regarding moral rights or reasons related to conscientious refusal, and none of the latter are found to support the notion of a legal right. Reasons for allowing some sort of room for conscientious refusal for healthcare professionals based on the importance of cultural identity and the fostering of a critical atmosphere might provide some support, if no countervailing factors apply. One such factor is that a legal right to healthcare professionals’ conscientious refusal must comply with basic legal ethical tenets regarding the rule of law and equal treatment, and this requirement is found to create serious problems for those wishing to defend the idea under consideration. We conclude that the notion of a legal right to conscientious refusal for any profession is either fundamentally incompatible with elementary legal ethical requirements, or implausible because it undermines the functioning of a related professional sector (healthcare) or even of society as a whole.

(Jan 2017) My Conscience May Be My Guide, but You May Not Need to Honor It

Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, Volume 26, Issue 1, January 2017 , pp. 44-58

Hugh LaFollette

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963180116000256

Abstract:

A number of healthcare professionals assert a right to be exempt from performing some actions currently designated as part of their standard professional responsibilities. Most advocates claim that they should be excused from these duties simply by averring that they are conscientiously opposed to performing them. They believe that they need not explain or justify their decisions to anyone, nor should they suffer any undesirable consequences of such refusal.

Those who claim this right err by blurring or conflating three issues about the nature and role of conscience, and its significance in determining what other people should permit them to do (or not do). Many who criticize those asserting an exemption conflate the same questions and blur the same distinctions, if not expressly, by failing to acknowledge that sometimes a morally serious agent should not do what she might otherwise be expected to do. Neither side seems to acknowledge that in some cases both claims are true. I identify these conflations and specify conditions in which a professional might reasonably refuse to do what she is required to do. Then I identify conditions in which the public should exempt a professional from some of her responsibilities. I argue that professionals should refuse far less often than most advocates do . . . and that they should be even less frequently exempt. Finally, there are compelling reasons why we could not implement a consistent policy giving advocates what they want, likely not even in qualified form.

(Dec 2016) Objection to Conscience: An Argument Against Conscience Exemptions in Healthcare

Alberto Giubilini

23 December 2016

https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12333

Abstract

I argue that appeals to conscience do not constitute reasons for granting healthcare professionals exemptions from providing services they consider immoral (e.g. abortion). My argument is based on a comparison between a type of objection that many people think should be granted, i.e. to abortion, and one that most people think should not be granted, i.e. to antibiotics. I argue that there is no principled reason in favour of conscientious objection qua conscientious that allows to treat these two cases differently. Therefore, I conclude that there is no principled reason for granting conscientious objection qua conscientious in healthcare. What matters for the purpose of justifying exemptions is not whether an objection is ‘conscientious’, but whether it is based on the principles and values informing the profession. I provide examples of acceptable forms of objection in healthcare.

Source: Bioethics

(Fall 2016) Accommodating Conscientious Objection in Medicine-Private Ideological Convictions Must Not Trump Professional Obligations

By Udo Schuklenk

J Clin Ethics. 2016 Fall;27(3):227-232.

Abstract: The opinion of the American Medical Association (AMA) Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs (CEJA) on the accommodation of conscientious objectors among medical doctors aims to balance fairly patients’ rights of access to care and accommodating doctors’ deeply held personal beliefs. Like similar documents, it fails. Patients will not find it persuasive, and neither should they. The lines drawn aim at a reasonable compromise between positions that are not amenable to compromise. They are also largely arbitrary. This article explains why that is the case. The view that conscientious objection accommodation has no place in modern medicine is defended.

Source: Journal of Clinical Ethics

(Sept 2016) Doctors Have no Right to Refuse Medical Assistance in Dying, Abortion or Contraception

Julian Savulescu and Udo Schuklenk

First published: 22 September 2016

https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12288

Abstract

In an article in this journal, Christopher Cowley argues that we have ‘misunderstood the special nature of medicine, and have misunderstood the motivations of the conscientious objectors’.1 We have not. It is Cowley who has misunderstood the role of personal values in the profession of medicine. We argue that there should be better protections for patients from doctors’ personal values and there should be more severe restrictions on the right to conscientious objection, particularly in relation to assisted dying. We argue that eligible patients could be guaranteed access to medical services that are subject to conscientious objections by: (1) removing a right to conscientious objection; (2) selecting candidates into relevant medical specialities or general practice who do not have objections; (3) demonopolizing the provision of these services away from the medical profession.

Read full article: Wiley Online Library

(June 2016) Conscientious Objection in Healthcare Provision: A New Dimension

Peter West-Oram and Alena Buyx

Bioethics 2016 Jun;30(5):336-43. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12236

Abstract

The right to conscientious objection in the provision of healthcare is the subject of a lengthy, heated and controversial debate. Recently, a new dimension was added to this debate by the US Supreme Court’s decision in Burwell vs. Hobby Lobby et al. which effectively granted rights to freedom of conscience to private, for-profit corporations. In light of this paradigm shift, we examine one of the most contentious points within this debate, the impact of granting conscience exemptions to healthcare providers on the ability of women to enjoy their rights to reproductive autonomy. We argue that the exemptions demanded by objecting healthcare providers cannot be justified on the liberal, pluralist grounds on which they are based, and impose unjustifiable costs on both individual persons, and society as a whole. In doing so, we draw attention to a worrying trend in healthcare policy in Europe and the United States to undermine women’s rights to reproductive autonomy by prioritizing the rights of ideologically motivated service providers to an unjustifiably broad form of freedom of conscience.

Source: Bioethics

(April 2016) Why medical professionals have no moral claim to conscientious objection accommodation in liberal democracies

Udo Schuklenk, Ricardo Smalling

BMJ Journal of Medical Ethics

April 27, 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2016-103560

Abstract:

We describe a number of conscientious objection cases in a liberal Western democracy. These cases strongly suggest that the typical conscientious objector does not object to unreasonable, controversial professional services—involving torture, for instance—but to the provision of professional services that are both uncontroversially legal and that patients are entitled to receive. We analyse the conflict between these patients’ access rights and the conscientious objection accommodation demanded by monopoly providers of such healthcare services. It is implausible that professionals who voluntarily join a profession should be endowed with a legal claim not to provide services that are within the scope of the profession’s practice and that society expects them to provide. We discuss common counterarguments to this view and reject all of them.

Source: BMJ Journal of Medical Ethics

(Nov 2015) The right to die and the medical cartel

M. Cholbi

19 November 2015

Ethics, Medicine, & Public Health

Summary

Advocates of a right to die increasingly assert that the right in question is a positive right (a right to assistance in dying) and that the right in question is held against physicians or the medical community. Physician organizations often reply that these claims to a positive right to die should be rejected on the grounds that medicine’s aims or ‘‘internal’’ norms preclude physicians from killing patients or assisting their patients in killing themselves. The aim of this article is to rebut this reply. Rather than casting doubt on whether assisted dying is consistent with medicine’s ‘‘internal’’ norms, I draw attention to the socioeconomic contexts in which contemporary medicine is practiced. Specifically, contemporary medicine typically functions as a public cartel, one implication of which is that physicians enjoy a monopoly on the most desirable life-ending technologies (fast acting lethal sedatives, etc). While there may be defensible public health reasons for medicine functioning as a cartel and having this monopoly on desirable life-ending technologies, Rawlsian contract-based reasoning illustrates that the status of medicine as a cartel cannot be reconciled with its denying the public access to supervised use of desirable life-ending technologies. The ability to die in ways that reflect one’s conception of the good is arguably a primary social good, a good that individuals have reasons to want, whatever else they may want. Individuals behind Rawls’ veil of ignorance, unaware of their health status, values, etc, will thus reason that they may well have a reasonable desire for the life-ending technologies the medical cartel currently monopolizes. They thus have reasons to endorse a positive right to physician assistance in dying.

On the assumption that access to desirable life-ending technologies will be controlled by the medical community, a just society does not permit that community to deny patients access to these technologies by an appeal to medicine’s putative ‘‘internal’’ aims or norms. The most natural response to my Rawlsian argument is to suggest that it only shows that individuals have a positive right against the medical community to access life-ending technologies but not a right to access such technologies from individual physicians. Individual physicians could still refuse to provide such technologies as a matter of moral conscience. Such claims of conscience should be rejected, however. A first difficulty with this proposal is that it is in principle possible for a sufficiently large number of individuals within a profession to invoke claims of conscience so as to materially hinder individuals from exercising their positive right to die, as appears to be the case in several jurisdictions with respect to abortion and other reproductive health treatments. Second, unlike conscientious objectors to military service, physicians who conscientiously object to providing assistance in dying would not be subject to fundamental deprivations of rights if they refused to provide assistance. Physicians who deny patients access to these technologies use their monopoly position in the service of a kind of moral paternalism, hoarding a public resource with which they have been entrusted so as to promote their own conception of the good over that of their patients.

Source: Academia.edu

(2015) Conscientious Objection in Medicine: private ideological convictions must not supercede public service obligations

“The very idea that we ought to countenance conscientious objection in any profession is objectionable.”

U. Schuklenk

Bioethics ISSN 0269-9702 (print); 1467-8519 (online) doi:10.1111/bioe.12167

Volume 29 Number 5 2015 pp ii–iii

Canada’s Supreme Court decided that Canadians’ constitutional rights are violated by the criminalisation of assisted dying. Canada’s politicians are currently scrambling to come up with an assisted dying regime within the 12 month period that the Supreme Court gave them to fix the problem.

Since then, the Canadian Medical Association, the country’s doctors’ lobby organisation, has insisted not only that doctors must not be forced to provide assisted dying but also that doctors must not be required to transfer patients asking for assisted dying on to a colleague who they know will oblige these patients.

In many countries, including Canada, conscientious objection clauses protect – mostly – healthcare professionals from being forced to act against their individual ideological convictions. I suspect it isn’t unfair to note that these protections in the real world are nothing other than protections for Christian doctors who are unwilling to deliver services they would be obliged to deliver to patients who are legally entitled to receive these services, were it not for their religiously motivated objections.

Secular healthcare professionals could arguably avail themselves of conscience clauses, but in a liberal democracy, what reasonable conscience-based cause could they have to refuse the provision of healthcare services to patients? Conscience clauses today are by and large a concession of special rights to Christian healthcare professionals, at least in secular Western democracies.

Read full article: www.academia.edu

(2015) Health care providers’ perceptions of and attitudes towards induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia

Subtitle: A systematic literature review of qualitative and quantitative data

Ulrika Rehnström Loi, Kristina Gemzell-Danielsson, Elisabeth Faxelid, and Marie Klingberg-Allvin

BMC Public Health (2015) 15:139

DOI 10.1186/s12889-015-1502-2

Partial Abstract:

Background: Unsafe abortions are a serious public health problem and a major human rights issue. In low-income countries, where restrictive abortion laws are common, safe abortion care is not always available to women in need. Health care providers have an important role in the provision of abortion services. However, the shortage of health care providers in low-income countries is critical and exacerbated by the unwillingness of some health care providers to provide abortion services. The aim of this study was to identify, summarise and synthesise available research addressing health care providers’ perceptions of and attitudes towards induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia.

Conclusions: Health care providers in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia have moral-, social- and gender-based reservations about induced abortion. These reservations influence attitudes towards induced abortions and subsequently affect the relationship between the health care provider and the pregnant woman who wishes to have an abortion. A values clarification exercise among abortion care providers is needed.

Relevant Excerpt:

Access to safe, legal induced abortion, postabortion care (which occurs after an unsafe abortion) and family planning is fundamental to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity related to unsafe abortions [64,65]. The conservative attitudes towards induced abortions among health care providers in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia might also affect access to post-abortion care and, consequently, post-abortion contraceptive counselling.

It is essential to highlight that the majority of the studies included in this review were conducted in South Africa, where it is known that many health care providers are conscientious objectors to the provision of safe abortions [17,66]. The refusal to assist in abortion services is frequently based on moral, religious, ethical or philosophical beliefs. As reported elsewhere, such conscientious objections to abortion provision are an abuse of women’s rights and potentially harmful to women’s health [67]. A recent study from Ghana indicates that a favourable attitude toward abortion among health care providers’ is not associated with safe abortion provision. On the other hand, it was noticed that the odds of providing safe abortions lowers by 57 percent when the health care provider is Catholic in comparison to other religions. Furthermore, the same study found that providers’ confidence in their capability to offer safe abortion is fundamental [68].

Source: BMC Public Health

(June 2014) The paradox of conscientious objection and the anemic concept of ‘conscience’

The paradox of conscientious objection and the anemic concept of ‘conscience’: downplaying the role of moral integrity in health care.

Giubilini A.

Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, June 2014, Vol. 24, No. 2, 159-185, by Johns Hopkins University Press

Abstract

Conscientious objection in health care is a form of compromise whereby health care practitioners can refuse to take part in safe, legal, and beneficial medical procedures to which they have a moral opposition (for instance abortion). Arguments in defense of conscientious objection in medicine are usually based on the value of respect for the moral integrity of practitioners. I will show that philosophical arguments in defense of conscientious objection based on respect for such moral integrity are extremely weak and, if taken seriously, lead to consequences that we would not (and should not) accept. I then propose that the best philosophical argument that defenders of conscientious objection in medicine can consistently deploy is one that appeals to (some form of) either moral relativism or subjectivism. I suggest that, unless either moral relativism or subjectivism is a valid theory–which is exactly what many defenders of conscientious objection (as well as many others) do not think–the role of moral integrity and conscientious objection in health care should be significantly downplayed and left out of the range of ethically relevant considerations.

(July 2012) Annotation of Prof. Carlo Flamigni, in “Conscientious Objection and Bioethics”

Annotation of Prof. Carlo Flamigni, in “Conscientious Objection and Bioethics, Presidency of the Council of Ministers, Comitato Nazionale per la Bioetica (CNB).

Translated from “Obiezione di Conscienza e Bioeteca,” Pesidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri.

12 July 2012

This Italian report from the National Committee of Bioethics declares “conscientious objection” in healthcare to be an “inviolable” human right for objectors. Out of the mostly Catholic committee of 24 persons, only one voted against the report – Professor Carlo Flamigni. He wrote a 13-page “Annotation” criticizing the report. Some excerpts from his Annotation:

“Supported by the Catholic Church, pro-life movements have been calling for years for the practice of conscientious objection to voluntary abortion to be recognized as an institution of constitutional rank and for it to be recognized as an ‘inviolable human right’. Punctually, the National Committee for Bioethics has now satisfied this request…”

“[To paraphrase the report’s language in simpler terms] conscientious objection to voluntary abortion (and in the future, who knows, to euthanasia) is something so noble and virtuous that the objector must be guaranteed the right to refrain from performing the (public) service required by law without any burden, ignoring the freedoms and fundamental rights of citizens who are entitled to receive that service.”

“The final conclusion is that if one abandons – as I believe it is necessary to do – the idea that conscientious objection should be considered as the banner raised in defence of human rights and in particular of the ‘right to life’ in the prenatal phase against a law enacted by a Creon [autocratic] power, then conscientious objection in the field of health is no longer a “fundamental right”, but it may be permitted provided that the objector is obliged to accept an appropriate charge (to provide a supplementary service that integrates the lack of service due, or to adopt the criterion of staff mobility cannot be adequate compensation) that testifies to the solely and exquisitely moral reasons for his request. Continuing to defend the current situation, which is limited to exempting from the service anyone who requests it, means defending the privilege of too many ‘convenient objectors’, i.e. continuing to feed the widespread immorality.”

Sources: Original Italian report http://bioetica.governo.it/media/1839/p102_2012_obiezione_coscienza_it.pdf

English translation (using Deepl Translate)

(2010) Emergency Contraception and Conscientious Objection

J. Paul Kelleher

Journal of Applied Philosophy, Vol 27, No. 3, 2010.

Abstract

Emergency contraception — also known as the morning after pill — is marketed and sold, under various brand names, in over one hundred countries around the world. In some countries, customers can purchase the drug without a prescription. In others, a prescription must be presented to a licensed pharmacist. In virtually all of these countries, pharmacists are the last link in the chain of delivery. This article examines and ultimately rejects several standard moves in the bioethics literature on the right of pharmacists conscientiously to refuse to dispense emergency contraception. Its central thesis is that the standard ‘moderate’ solution to this problem is mistaken. Thus, when all publicly relevant interests are given their due, it is not acceptable to allow refusals in the big city, where pharmacies are plentiful, but forbid them in rural settings, where pharmacies are scarce. Rather, there should be strong public policy requiring that all pharmacists dispense emergency contraception to customers who request it, regardless of pharmacists’ moral or religious objections.

Source: Journal of Applied Philosophy

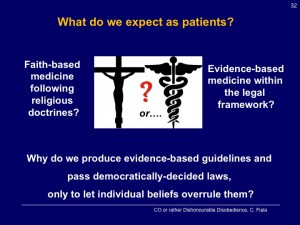

(Nov 2009) Denial of Abortion Care Information, Referrals, and Services Undermines Quality Care for U.S. Women

Tracy A. Weitz and Susan Berke Fogel

9 November 2009

Women’s Health Issues 20 (2010) 7–11

On September 9, 2009, President Barack Obama spoke before a joint session of Congress on the imminent need for health care reform. In his speech, he addressed the contested social issue of abortion in two ways: by reaffirming the ongoing exclusion of abortion from federal health care financing and supporting health care providers’ right to opt out of providing health care they find objectionable. “I want to clear up—under our plan, no federal dollars will be used to fund abortions, and federal conscience laws will remain in place” (Obama, 2009). His acceptance of the right to deny health care for ideological reasons directly contradicts the expectation most Americans share—that the care they receive will be consistent with the highest standards of scientific evidence, based on individual patient need, and with the goal of maximizing health and wellness.

This commentary provides a brief investigation into this contradiction by providing a new way of thinking about health care denials using the same yardsticks employed to assess health care quality more generally: the adherence to evidence-based standards of care, a commitment to patient centeredness, and focus on prevention of poor health outcomes (Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2001). The contents of this commentary are drawn from a report to be released by the National Health Law Program, Health Care Refusals: Undermining Quality Care for Women (Fogel & Weitz, 2009). Although the full report addresses broader needs for care related to pregnancy prevention, pregnancy termination, fertility achievement, and healthy sexuality, this commentary is limited to a few standards of care that necessitate abortion as a health care option for women.

Source: ANSIRH.org

(2009) Conscious Oppression: Conscientious Objection in the Sphere of Sexual and Reproductive Health

Marcelo Alegre

SELA (Seminario en Latinoamérica de Teoría Constitucional y Política) Papers. Paper 65. 2009.

Abstract

Although for centuries conscientious objection was primarily claimed by those who for religious or ethical reasons refused to join the ranks of the military (whether out of a general principle or in response to a particular violent conflict), in recent decades a significant broadening of the concept can be seen. In Thailand, for example, doctors recently refused medical attention to injured policemen suspected of having violently repressed a demonstration. In Argentina a few public defenders have rejected for conscientious reasons to represent individuals accused of massive human rights violations. In different countries all over the world there are doctors who refuse to perform euthanasia, schoolteachers who reject to teach the theory of evolution, and students who refuse to attend biology classes where frogs are dissected.

Comments: Paper delivered at SELA 2009, Law and Sexuality, in Asunción, Paraguay, as part of the panel on “The Foundational Ideals.”

Download full article

(Feb 2009) The Personal is Political, the Professional is Not: Conscientious Objection to Obtaining/Providing/Acting On Genetic Information

by Joel Frader and Charles L. Bosk

15 February 2009

Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet, 151C(1): 62–67, doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30200

Abstract:

Conscientious objection (CO) to genetic testing raises serious questions about what it means to be a health care professional (HCP). Most of the discussion about CO has focused on the logic of moral arguments for and against aspects of CO and has ignored the social context in which CO occurs. Invoking CO to deny services to patients violates both the professional’s duty to respect the patient’s autonomy and also the community standards that determine legitimate treatment options. The HCP exercising the right of CO may make it impossible for the patient to exercise constitutionally guaranteed rights to self-determination around reproduction. This creates a decision-making imbalance between the HCP and the patient that amounts to an abuse of professional power. To prevent such abuses, professionals who wish to refrain from participating have an obligation to warn prospective patients of their objections prior to establishing a professional-patient relationship or, if a relationship already exists, to arrange for alternative care expeditiously.

(Feb 2006) The Priority of Professional Ethics Over Personal Morality

by Rosamond Rhodes

Published 02 February 2006

BMJ 2006;332:294

doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7536.294

(Response to Julian Savulescu’s article “Conscientious objection in medicine”, 2006)

To understand the social role of medicine and its ethics, it is important to recognize that the medical profession is a social artifact created by giving control over a set of knowledge, skills, powers and privileges exclusively to a select few who are entrusted to provide their services in response to the community’s needs and to use their distinctive tools for the good of patients and society. Although a good deal of medicine involves preventing or healing disease and or restoring function, defining medicine narrowly in those terms leaves out numerous medical roles. For example, we call upon medicine for the provision of

prenatal care and birth control, even when no one is ill. We call upon medicine to ameliorate a dying patient’s suffering, even when the disease cannot be healed nor function restored.

Read full response: the BMJ

(2006) Conscientious objection in medicine

by Julian Savulescu

BMJ. 2006 Feb 4; 332(7536): 294–297.

doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7536.294

Short abstract: Deeply held religious beliefs may conflict with some aspects of medical practice. But doctors cannot make moral judgments on behalf of patients

Shakespeare wrote that “Conscience is but a word cowards use, devised at first to keep the strong in awe” (Richard III V.iv.1.7). Conscience, indeed, can be an excuse for vice or invoked to avoid doing one’s duty. When the duty is a true duty, conscientious objection is wrong and immoral. When there is a grave duty, it should be illegal. A doctors’ conscience has little place in the delivery of modern medical care. What should be provided to patients is defined by the law and consideration of the just distribution of finite medical resources, which requires a reasonable conception of the patient’s good and the patient’s informed desires (box). If people are not prepared to offer legally permitted, efficient, and beneficial care to a patient because it conflicts with their values, they should not be doctors. Doctors should not offer partial medical services or partially discharge their obligations to care for their patients.

Read full article: NCBI/NLM

(1993) Futile care. Physicians should not be allowed to refuse to treat. Point.

Robert M. Veatch, and Carol Mason Spicer

Health Prog. 1993 Dec;74(10):22-7.

Abstract:

Eighteen years after the era of Karen Ann Quinlan, the debate over futile care has shifted. Now some patients are asking for treatment that care givers believe to be useless. In virtually all cases of so-called futile care, the real disagreement is not over whether a treatment will produce an effect; it is over whether some agreed-on potential effect is of any value. An obvious reason to resist providing care believed to be futile is that is appears to consume scarce resources and therefore burden others. However, for care that affects the dying trajectory but appears to most of us to offer no benefit, the proper course is for society–not clinicians–to cut patients off. Under certain circumstances patients should have the right to receive life-prolonging care from their clinicians, provided it is equitable funded, even it the clinicians believe the care is futile and even if it violates their conscience to provide it. Society is not in a position to override a competent patient who prefers to live even if life prolongation is burdensome. For incompetent patients, if a clinician believes a treatment is actually hurting a patient significantly, he or she may appeal to a court to have it stopped. A society that forces people to die against their will produces more offense than one that forces healthcare providers to provide services that violate their conscience. And medical professionals have a social contract with society to control the use of medical, life-prolonging technologies.

Read full article (PDF): Health Progress